"Out with the Old, in with the New"

- David Mansfield

- Dec 10, 2024

- 13 min read

With the ephedra season now drawn to a close and the poppy planting season in full swing, it is an ideal time to assess the impact of the Taliban drug ban on the methamphetamine and opium industries, as well as the implications for the rural economy, and the political stability of Afghanistan.

In 2024, evidence shows that the transformation of the methamphetamine industry is almost complete. In the wake of continued pressure from the Taliban, the district of Bakwa in southwest Afghanistan has been converted from a market hub for ephedra and ephedrine production during the Islamic Republic period to a trading centre for ephedrine and the production of methamphetamine. It is an industry that has now largely relocated into the central highlands and is producing markedly less than before but whose methamphetamine output remains far more than what is seized downstream.

Typically, the opium trade remains robust. While there have been two consecutive years of a poppy ban, leading to record low levels of cultivation, trade has continued, drawing on the substantial amounts of opium that had been stored from excess production during the Republic and the first year of Taliban rule. However, with the poppy planting season now in progress, the unseasonal fall in the price of opiates highlights the growing market uncertainty around the drugs trade in Afghanistan; these shifting dynamics are not only a result of the Taliban ban but also of broader geopolitics and its impact on cross-border trade with Pakistan and Iran.

Reduced volumes and increasing uncertainty in the markets for both opiates and meth

From the peak ephedra harvest in 2021, methamphetamine production has fallen every year due to the increased restrictions the Taliban has imposed on the industry. While there is no baseline for production data at the national level for 2021, nor annual assessments since then, those involved at each stage of the value chain - from the harvesting of ephedra in the central highlands to the labs producing methamphetamine in the southwest – now operate in secrecy, working at night, for fewer days than in the past, and producing smaller volumes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. From 2017 until December 2021, large volumes of ephedra were stored in open ground in Abdul Wadood Bazaar in Bakwa District, Farah, in southwest Afghanistan. On 26 November 2021, an estimated 11,8666 cubic metres were found in the bazaar, the equivalent of 220 metric tons of methamphetamine. In early December 2021 the Taliban banned the harvest of ephedra and its trade. Since early February 2022, no ephedra stores have been found in the bazaar.

In contrast to 2021 and early 2022, high-resolution satellite imagery shows ephedrine production in much smaller labs in 2024 and increasingly located in more remote areas as the Taliban extend their reach and push the ban further into the central highlands (see Figures 2 and 3). So, in contrast to during the Republic when “business was free”, the methamphetamine industry is now high-risk, with a growing number of those involved having direct experience of the seizure and destruction of their product.

Figure 2: In 2021 and early 2022, when the methamphetamine industry in Afghanistan was at its peak, and ephedrine production continued unrestrained, ephedrine labs were large, operated every day and were primarily located in Bakwa in the area surrounding Abdul Wadood bazaar. Since the Taliban ban, labs have relocated to the central highlands, where they work with much smaller batch sizes and fewer days, and they are subject to shorter seasons due to the cold winters.

Figure 3. As the Taliban ban on the ephedra harvest and production of ephedrine increases, those involved move further into the mountains to ever more isolated areas.

Nevertheless, despite increased risks and costs due to the Taliban ban, Afghanistan continues to produce substantial amounts of methamphetamine, far exceeding what is seized downstream. Even with smaller batches, reduced work rates, and a shorter season, labs in the central highlands produce between 400 and 900 kilogrammes of ephedrine per year, the equivalent of 320 to 720 kilogrammes of methamphetamine. This compares to the potential production of the equivalent of 1,568 to 4,480 kilogrammes of methamphetamine from the much larger ephedrine labs found in Bakwa in the southwest in 2021 and early 2022, which operated for up to eight months per year and were unhindered by snows and the cold temperatures that besiege the central highlands (see Figure 4).

Even at the much-reduced levels of productivity that are typical in 2024, it would take between 24 and 55 ephedrine labs to produce the equivalent of the 21,900 kilogrammes of meth, a record amount, seized by Turkey in 2023. Moreover, imagery analysis has identified 154 ephedrine labs in a limited number of areas in seven districts of Afghanistan and a further 15 in Bakwa (See Figure 5). With 73 districts across 17 provinces in Afghanistan showing some evidence of either ephedra or ephedrine trade, production remains far more than what has been seized in Iran and Turkey each year (see Figure 6).

Figure 4. Although, the "mega labs" that were seen in Bakwa in 2021, and early 2022 are a thing of the past, and the Taliban ban has made it more difficult to operate, the ephedrine labs in the central highlands can still produce up to 900 kilogrammes of ephedrine per year.

Figure 5. It was 2018 when ephedrine labs first began relocating from Bakwa in the southwest to the central highlands, following several raids by Afghan and US forces raided. However, the process accelerated following the Taliban ban in late December 2021 and their closure of Abdul Wadood Bazaar and the surrounding labs in September 2022.

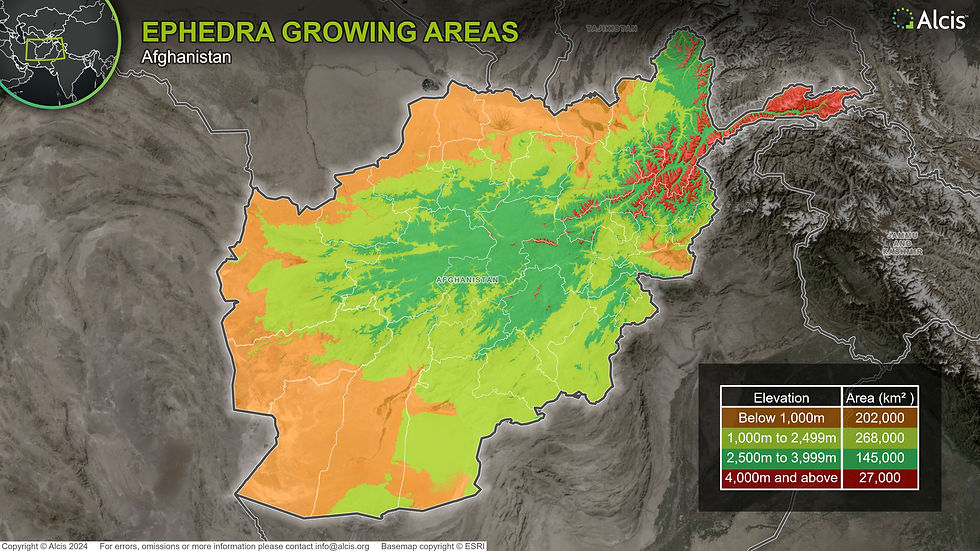

Figure 6. Ephedra can be found at different altitudes in Afghanistan, but the variety preferred by traders and cooks for its high ephedrine content, grows at 2500 metres and above. There is no shortage of areas where it grows and the crop remains abundant across the central highlands.

Ephedra continues its primacy as the precursor of choice, offering major advantages for the production of high-quality methamphetamine at scale. The use of Over-the-Counter (OTC) Medicines in the production of methamphetamine in Afghanistan is not cost-effective and stopped many years ago. It requires greater skill, incurs higher costs (more than $400 per kilogramme for the cook and tablets alone), and results in lower productivity (3-7 kg per day).

Around 2017, the shift to ephedra-based production created a cottage industry where larger volumes of ephedrine (14 kilogrammes per day) could be produced by cooks with only a rudimentary knowledge of chemistry at a much lower cost (US$ 100 per kilogramme). This allowed more accomplished cooks to focus on converting the ephedrine produced into high-quality methamphetamine and the production to scale up in Afghanistan. Seizures off the Makran coast near Pakistan, a common smuggling route for drugs from Afghanistan, show purity rates of ephedra-based methamphetamine of at least 95% (see Figure 7). No reports of bulk Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (API) used in Afghanistan or seizures support the claim that this is a current production method.

Figure 7. The best quality Afghan methamphetamine is pure white, hard and “shines”. Some of these crystals, known as “radi” or rods, can be up to 25 cm long and 5 cm wide and are more durable.

Recent falls in the price of ephedra, ephedrine, and methamphetamine, despite falling production, as well as declining orders from Iran, reflect the current uncertainty in the drugs market in Afghanistan and the region (see Figure 8). The same can be seen with opiates, where prices continue to fall despite the second consecutive year of low levels of cultivation, and in stark contrast to what would typically be expected in the run-up to planting season (see Figure 9).

Figure 8. Despite reduced volumes, the price of methamphetamine in Afghanistan has fallen since mid-2023. Between September 2022, when the Taliban closed down Abdul Wadood, until June 2023, the price rarely fell below US$600 per kilogramme. In November 2024, the price was US$350 per kilogramme, resulting in further declines in the price of ephedrine and ephedra.

Figure 9. The price increases that are typically seen in the planting season have not materialised in the fall of 2024, even after two consecutive years of low levels of poppy in Afghanistan, highlighting the increasing uncertainty in the market for opium and its derivatives in Afghanistan.

It is likely that reports of extensive poppy planting in Badakhshan in October and November 2024, the prospect of further opium production in Pakistan this planting season, and the substantial inventories in southwest Afghanistan have further depressed prices (see Figure 10). However, it is also possible that traders are looking to avoid the market overreaction in late 2023, when prices rose to almost US$1,100 per kilogramme in the southwest, only to fall to US$600 in the summer of 2024.

Figure 10. Poppy cultivation in Pakistan increased in 2022 and 2023 following the imposition of the Taliban ban in Afghanistan. While cultivation is constrained in Khyber District due to small landholdings, there are signs of much more extensive poppy cultivation in the parts of Balochistan, where former desert areas have been settled and brought under cultivation.

Up until now, the substantial inventory with farmers in the southwest, combined with the frequency and degree to which opium and its derivatives are adulterated for markets in the region, has ensured a continued supply of heroin to European markets even after two years of limited poppy cultivation in Afghanistan (see Figure 11 and 12). However, other factors are increasing uncertainty in the drugs market and possibly resulting in traders deferring their transactions until the planting season has finished. This includes a significant depreciation in the Iranian Rial and fears of growing political instability in Iran, as well as further restrictions by the Taliban on drugs smuggling within Afghanistan and on its borders.

Figure 11. Opium ordered for consumers in Iran is typically adulterated with a mix of caffeine, Anjaroot (a type of fruit), and Zerha chakai (unknown), at a ratio of 3:1. Traders test the final product to ensure that they have not added too much of the powdered mix to the opium.

Figure 12. In this case the mix is added to the opium while it is dried in the sun, it can be seen on the right hand of the individual as the opium is spread across the “taat” tarpaulin.

You win some, you lose some

The economic effects of the contraction in the drugs economy are uneven. In the methamphetamine industry, the downturn impacts those along the length of the value chain, with the most significant adverse economic effects in the central highlands where ephedra is harvested and ephedrine production is concentrated (see Figure 13). Communities in these areas have seen a significant reduction in income since the Taliban imposed restrictions on ephedra and ephedrine production in late 2021. This is primarily because although prices have risen due to tightening enforcement of the Taliban drugs ban, they have not increased at a rate to compensate for much lower production levels.

Figure 13. The methamphetamine industry restructured following the Taliban’s closure of Abdul Wadood Bazaar, and the ephedrine labs that surrounded it. Now ephedrine is produced in the central highlands in more discrete labs which work with much smaller batch sizes.

Moreover, those involved at each stage of the methamphetamine value chain are increasingly concealing their efforts, working at night, with smaller batches, and in more remote areas (see Figure 14). This has raised production costs and risks, reduced profits, and deterred some from continuing their operations, further impacting the local economy in the central highlands, where economic opportunities are sparse in the first place.

Figure 14. Ephedrine labs are much more discrete than they were during the Republic, with cooks and owners better managing the run-off of liquid waste and the storage of inputs and physical waste, so the lab cannot easily be identified.

Reports of extensive poppy planting in Badakhshan this fall highlight the economic challenges communities face when a ban is imposed in the absence of viable alternatives, especially in more remote mountainous areas. In contrast to wealthier landed farmers in the south and southwest, farmers in the northeast live in remote localities, have small landholdings, and therefore cultivated smaller poppy fields even when the environment was more permissive and there was no Taliban ban. Thus, these farmers have had few opportunities to accumulate the stocks of opium found in the southwest, which have increased in value following the Taliban ban.

Under these conditions, farmers in places like Badakhshan find it difficult to meet basic needs in the absence of poppy, and cultivation will be more persistent despite increased coercion not to plant. There is a risk that these economic factors, combined with the political dynamics in Badakhshan, where there are tensions between the Pashtoon-dominated Taliban leadership, local elites and the rural population, will increase the potential for violence and more widespread unrest if the Taliban mount an aggressive campaign to destroy the poppy crop completely.

Yet, despite the downturn in both the opiate and the methamphetamine economy, there is no sign of a resulting increase in irregular outmigration this fall. Cross-border movements from Afghanistan into Iran directly and through Pakistan have become more dangerous with increased border security by Tehran, as well as Iranian border guards’ indiscriminate shootings (see Figure 15). Inside Iran, there is a growing hostility to Afghan migrants, fuelled by a deteriorating economy and a new President. However, migration and remittances from Iran and Pakistan have been an important safety valve for Afghan households with limited economic opportunities in-country. A downturn in both the drugs economy and outmigration presents a serious and growing challenge for those in Afghanistan with few economic alternatives.

Figure 15. The cost of smuggling across the Afghanistan-Iran border has increased dramatically following the outbreak of fighting between the two countries in May 2023. Costs have steadily increased as the border forces in both Nimroz and Sistan Balochistan have sought to deter smugglers from operating and avoid a repeat of last years violence.

Uneven rule and the signs of fragility

Perhaps we should not be surprised that authoritarian rulers are more effective at imposing restrictions on the production of and trade in drugs than other, more democratic systems. Indeed, the Taliban have proven able to extend their writ into the central highlands and push restrictions on the methamphetamine industry into ever more remote areas, unsettling the local arrangements that had allowed production to continue. However, imposing a complete ban on methamphetamine presents a challenge to the Taliban, given the remote mountainous terrain where ephedra grows and ephedrine production is now located.

Nevertheless, this year, the ban was extended, including in parts of Ghor, where the appointment of a new Governor undermined the prevailing patronage systems.

This may be only a temporary cessation of production, as local communities and elites negotiate with the new Governor, and perhaps then restart their business in July 2025 when the next ephedra season begins. It could, however, also be a more lasting development, and the new Pashtoon Governor might attempt to enforce wider compliance with Haibatullah’s drug ban, undermining the economic interests of the Aimaq tribal groups that dominate the Taliban leadership in Ghor. If it is the latter, it could also prove destabilising.

Clearly, reports of extensive poppy cultivation in Badakhshan this fall will test the Taliban as they look to avoid a repeat of the violent unrest prompted by eradication efforts in the spring of 2024 and the example that it could set for other areas looking to return to poppy. The recent redeployment of a local Badakshi Army unit to lead the counternarcotics efforts in Badakhshan reflects a degree of caution amongst the Taliban leadership and a desire to avoid last year’s unrest and the underlying ethnic tensions that proved incendiary. Given the economic pressures in this remote mountainous province in the absence of viable alternatives, it is likely that the Taliban will look to find some kind of compromise that mitigates the risk of widespread dissent.

This could include a policy of “forbearance” for poppy cultivation in the more remote (and less high-yielding) rainfed areas, with only nominal efforts to eradicate in the spring. Widespread cultivation in lower, more accessible, irrigated and high-yielding areas would prove more difficult to conceal from the Taliban leadership and the international community. It could also encourage others in Badakhshan to flout the ban and could provoke a more aggressive reaction from the Taliban that might involve soldiers from outside (including Pashtoons). The evidence of planting in these irrigated areas reflects the continued challenges the Taliban face in Badakhshan, with a much greater risk of violent unrest if they defer eradication until the spring of 2025, when many more might have planted poppy, and farmers would have sunk more investment into the crop.

Reports of a “summer” poppy crop in northern Helmand could point to further fractures in the ban, including in one of the Taliban’s core constituencies. Poppy planted in the southwest during the spring and summer is typically low-yielding and covers only a small area (typically less than 10,000 hectares). Nevertheless, the Taliban were quick to destroy these crops in April 2022, immediately after Haibatullah announced the drugs ban. This was despite allowing farmers to harvest the standing “fall” crop planted before the ban was imposed.

Without imagery, it is hard to know how extensive the summer crop was, but its reappearance two years after the ban was imposed could reflect the growing challenges the Taliban faces maintaining compliance from rural communities, especially in more remote and mountainous parts of northern Helmand. It might also be seen as a signal to rural communities in other areas that poppy cultivation could be tolerated, raising the likelihood of further planting this year in more remote parts of south and southwest Afghanistan.

Of particular interest is the unseasonal fall in opium prices and the impact this has had on the value of the inventories of the landed farmers of the southwest, as it is their political support that has been critical to the success of the poppy ban, and they remain a core constituency of the Taliban leadership. Were prices to continue to fall, it could jeopardize the poppy ban, undermining the economic position of this important group, possibly resulting in many returning to poppy cultivation. So far, landed farmers in the southwest have gained significant economic advantage from the poppy ban, and as long as prices are rising, they have little interest in returning to planting (see Figure 16).

However, this calculus could change if prices continue to fall and the Taliban further increases pressure on the opium trade. A return to widespread cultivation in the southwest by landed farmers would present the Taliban leadership with a significant challenge, especially given the former’s number and political influence (see Figure 17). Cultivating poppy would not only be viewed as failing to comply with Haibatullah’s religious edict but defying his leadership and would need to be handled carefully if it were not to stoke unrest in the Taliban heartlands. From the evidence so far, it seems imposing a drugs ban is one thing, but maintaining it can test even the most autocratic of regimes.

Figure 16. The amount of profit that a farmer earns on opium poppy depends on whether they own the land it is grown on, the mechanisms used to employ labour, and at what point in the year the crop is sold, with prices typically rising in the winter, months after the crop is harvested. Wealthier landed farmers employ sharecroppers who do most of the work, as poppy is a particularly labour-intensive crop, but who only get ¼ of the final crop. This allows the landed to retain much of the final yield, selling it only when prices rise. Following the announcement of the Taliban ban in April 2022, opium prices rose dramatically, giving those with stored opium a significant financial advantage.

Figure 17. In the south and southwest, there are almost 175,000 landed households – a population of around 1.75 million people- that have benefitted from the poppy ban due to the inventories of opium they accumulated and the dramatic rise in prices that followed the Taliban ban.

David Mansfield has been conducting research on illicit economies in Afghanistan and on its borders each year since 1997. David has a PhD in development studies and is the author of “A State Built on Sand: How opium undermined Afghanistan.” He has produced more than eighty research-based products on rural livelihoods and cross-border economies, many for the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, and working in close partnership with Alcis. David was also the lead researcher on the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction’s Counter Narcotics: Lessons from the US Experience in Afghanistan, covering the period from 2002- 2017.

Kommentare