A second consecutive year of a poppy ban in Afghanistan, but at what price?

In 2024, Afghanistan is experiencing an unprecedented second consecutive year of the Taliban’s poppy ban. This year, as in 2023, it is expected that poppy cultivation will be at close to historically low levels. For example, as of 22nd July, crop mapping of 14 of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces responsible for 92% of the country’s total poppy cultivation in 2022 shows that cultivation had fallen to less than 4,000 hectares in 2024, compared to around 16,000 hectares in 2023 and almost 202,000 hectares in 2022. However, there are notable exceptions that have the potential to challenge the Emir’s ban. In remote, northeastern Badakhshan, widespread cultivation persists, and eradication efforts have been met with violent resistance in which at least two citizens and three Taliban soldiers were killed. Resistance was further fuelled by perceptions of ethnic bias by the predominantly Pashtoon authorities and the sense that large farmers in south and southwest are profiting from the higher prices created by the ban.

While the Taliban authorities felt the need to project strength, resolve, and the appearance of a robust eradication campaign, they also feared unrest and the potential for increasing support for armed opposition groups in the province, prompting a compromise that allowed farmers to harvest much of their crop. While this concession might have tamped down the immediate possibility of spreading conflict, it could also create a demonstration effect and fuel unrest in other provinces where communities look to return to poppy. The events in Badakhshan and elsewhere, where farmers have responded to the ban by abandoning important cash crops, growing staple food crops such as wheat, and leaving land fallow, suggest the Taliban’s poppy ban is fragile and will become more difficult to enforce in the future. As has been observed over the years, a sustainable transition out of opium poppy requires a combination of reliable markets for cash crops (e.g., horticulture) and a substantial increase in non-farm income opportunities. Especially in remote areas such as Badakhshan, where jobs are scarce and where geography and the small size of land holdings limit the types of crops that can be grown, maintaining the ban runs the risk of further unrest and further outmigration.

Badakhshan: The exception that could become the rule?

It was almost inevitable that the Taliban leadership would feel the need to act against the poppy crop in the remote northeastern province of Badakhshan in 2024. The previous year, in contrast to all other provinces in Afghanistan, farmers in Badakhshan maintained high and increasing levels of poppy cultivation, ignoring Mullah Haibatullah’s edict of 3 April 2022 (see Figure 1). Despite the ban, the provincial and district authorities in Badakhshan had done little to dissuade farmers from planting poppy in the fall of 2022 and mounted a rather lacklustre eradication campaign in the spring of 2023 which was largely abandoned following a violent reaction in the districts of Jurm and Darayem.

In the absence of either viable agricultural alternatives, or sufficient non-farm income opportunities, and with dramatic increases in opium prices prior to the next planting season in the fall of 2023, there was always a strong likelihood that farmers in Badakhshan would continue with widespread poppy cultivation this year. However, in doing so, farmers and indeed the provincial and district authorities in Badakhshan became an exception that had to be quashed if they were not to become a challenge to the Emir’s poppy ban or to the perception of his absolute rule.

Figure 1: Map showing where and by how much poppy cultivation changed between 2022 and 2023. Red areas show a decrease in cultivation and green areas show an increase.

A changing of the provincial guard and the influx of Pashtoons

It could be argued that the move against the 2024 poppy crop in Badakhshan began in June 2023, with the removal of Governor Mullah Amanuddin Mansoor, a long-serving local Badakhshi Taliban commander who functioned as the shadow governor for Badakhshan during the insurgency and had held the official position since the Taliban captured the province in August 2021. He was replaced by Qari Mohammed Ayub Khalid, a Pashtoon from Kandahar who was transferred from Kunar.

It took some time for the counter-narcotics campaign in Badakhshan to begin in earnest this year. Despite his appointment in the summer, Governor Khalid did not arrive until December 2023, by which time the more significant winter crop had already been planted. Before his arrival, local officials had made some effort to deter planting in November and December 2023, sending letters to the districts and requesting that announcements be made in the mosques to warn farmers that their crops would be destroyed, a standard practice in advance of eradication campaigns. These were largely ignored, and it is alleged that some of the letters posted on the mosque walls were even torn down by farmers who argued that in the absence of jobs and alternative crops, they had no alternative to cultivate poppy.

Once the Governor had taken up his new post in Faizabad, things began to change. The new Governor announced a ban on the carrying of weapons; local Badakhshi commanders who had held senior positions in the provincial administration since the Taliban took power were transferred; and a growing number of Pashtoons were appointed in their place.

By early January 2024, even senior Taliban officials, including Qari Fasihuddin Fitrat, the Chief of Army Staff and most senior Badakhshi commander in the Taliban, and the person who would later be appointed as the head of the delegation responsible for investigating the instability caused by eradication, were expressing concern about the rise in poppy cultivation in Badakhshan.

Under a ban poppy is typically grown in relatively secluded areas but cultivation could now be seen in some of the most accessible areas, including near the airport and main road in Faizabad (see Figure 2). Despite these obvious signs that Mullah Haibatullah’s edict had once again been ignored in Badakhshan, it was not until the last few days of March 2024 that eradication really began. Of course, once the crop is in the ground, there is always a heightened risk that communities will resist efforts to destroy their poppy, especially when cultivation is widespread, the crop is already at an advanced stage, and a critical mass of farmers have planted.

Figure 2: Imagery analysis showing poppy cultivation around the airport and main road in Faizabad, Badakhshan.

Initially, eradication began in the immediate vicinity of the provincial centre of Faizabad, with the destruction of the crop in the villages nearby, as well as along the roadside. In early, April 2024, crop destruction took on a more menacing air with the appearance of the Deputy Governor, and an entourage of Taliban officials, on the outskirts of the city, tasked with spraying the poppy crop with herbicides (see Figure 3). Wearing full protective gear – a rare sight in rural Afghanistan, even in those areas where herbicides are commonly used - and carrying backpacks of liquid herbicide, Taliban soldiers began to spray the crop. Although clearly a “display for the cameras”, as there were no further reports of herbicides having been used, it did appear to represent a shift in attitude by the authorities as they began to step up the eradication effort in the districts.

Figure 3: Photo from social media and imagery showing the location of the Taliban’s ground spraying efforts in April 2024, on the outskirts of the city of Faizabad.

The need to act against the crop

In early May 2024, the authorities' desire to eliminate poppy in Badakhshan regardless of community concerns or economic situation, provoked open dissent, starting in the districts of Darayem and Argo, where cultivation and the opium trade are centred. In Darayem, the spark that lit the flame was Taliban efforts to destroy the poppy crop in the village of Qarluq on 3rd May 2024 where farmers met the eradication team with protests and stone-throwing.

In response, Taliban soldiers opened fire, killing an elderly man and injuring others. To make matters worse, in their efforts to arrest the protagonists, Taliban soldiers entered household compounds in the village, injuring female family members. The accusation that this was all done at the behest of Pashtoon soldiers from “other provinces” only fanned the flames of unrest, which quickly spread. The next day, in the village of Ganda Chishma in the neighbouring district of Argo, farmers also resisted efforts to destroy the poppy crop, and once again, Taliban soldiers opened fire, killing one and injuring five others.

Several days of demonstrations followed, involving an estimated 4,000 people who surrounded the district centre in Argo and closed the road to Faizabad (see Figure 4). Against the backdrop of major shifts in the balance of power in the provincial administration following the new Governor’s arrival, the dispute also took on a decidedly ethnic tone when those from Argo called for all Pashtoon soldiers to leave the area. More alarming to the Taliban leadership were public calls at these demonstrations for the “end to the Islamic Emirate”, and rumours circulating locally that the Taliban government in Badakhshan might fall.

Figure 4: Map with photo insets showing the location of eradication and subsequent protests in Argo and Darayem.

Local efforts to calm the situation achieved little, and with demonstrations running in parallel in Argo and Darayem on 6th May 2024, Prime Minister Mullah Hassan, sent a delegation of senior Taliban officials to the province to try and quell the unrest. On his arrival in Faizabad, Fasihuddin, the head of the delegation, sent the Deputy Governor, Aminullah Tayeb, an Uzbek, to negotiate with elders in Darayem and Argo to end the dispute.

Local demands were clear: all Pashto-speaking soldiers should be transferred from the area; only 50% of the crop should be destroyed; farmers should be compensated for their losses; and the families of those who had been killed should be compensated for the deaths of their loved ones. The next day, on 8th May 2024, elders from Argo presented these same demands to Fasihuddin in Faizabad. However, that same day, there was a bomb attack against a convoy of vehicles carrying soldiers heading to the district of Baharak to destroy the poppy crop. Claimed by the Islamic State Khorasan Province, the bomb killed three, and injured six.

A show of force

It is said that this attack shifted the dial for the Taliban. While Fasihuddin agreed to pay compensation to the families of those that had died – and Pashtoon soldiers were indeed withdrawn from Argo, elders were told eradication would continue, and there would be no exceptions. Typical of these situations, and as a means of buying both time and a degree of acquiescence from communities facing the loss of their crop, Fasihuddin is also said to have made promises of future development assistance for the district of Argo.

There is some confusion about the sequencing of events that followed these negotiations. Earlier claims made on 7th May 2024 by both Fasihuddin and Taliban spokesman Zabibullah Mujahid, that the dispute had been settled proved untrue; negotiations were, in fact, ongoing and even on 8th May 2024, demonstrations continued in both Argo and Darayem. In fact, an uneasy peace was reached, partly through a show of force, as the Taliban deployed additional soldiers in the area, and by restricting communications with the outside world, but also by conceding to farmers demands by limiting the eradication effort so that only a fraction of the crop was destroyed.

Certainly, any signs of continued resistance were quickly quashed, such as the outbreak of violence in the village of Barlas on 13th May 2024. Like earlier incidents, the cause appears to have been a clash between overzealous soldiers and a family looking to protect their livelihood. However, in contrast to the incidents earlier in the month, this time, the Taliban sealed the village, didn’t allow anyone to enter or leave, and mounted door-to-door searches to find the protagonists. The operation culminated in as many as 16 arrests and in a display of strength, the suspects being airlifted to Faizabad by helicopter.

Outwardly, the Taliban talked of a robust eradication campaign with few concessions; the picture, however, was more nuanced. While farmers’ demands for the withdrawal of Pashtoon soldiers were met in Argo, this was not the case elsewhere. In Jurm, there was an influx of soldiers from Baghlan, Kunduz, Samangan, and other provinces tasked with eradication. Determined not to lose face and fearing a repeat of the attack on the eradication convoy in Faizabad, these soldiers arrived in mid-May with a show of strength, deploying with up to 40 pick-up vehicles and securing a perimeter around the area. With a deep unease on both sides, villagers were not allowed and did not want to approach. Moreover, following the IED attack in Faizabad on 8th May 2024, those in the eradication team were deeply nervous and had little tolerance for any signs of resistance.

In contrast to 2023, local Taliban commanders in the districts also appear to have acquiesced and fallen in line with the eradication campaign and complied with the demands of Kabul and Kandahar. There were no reports of any kind of opposition despite the requests from farmers and elders. While the arrest of two soldiers of a Taliban commander in Jurm provoked some media attention and was viewed by some as indicative of a wider resistance. Locally it was largely dismissed as, either a mistake and the overreactions of Taliban soldiers ill at ease in the area, or the actions of two soldiers gone rogue, acting without the sanction of their commander.

Eradication in name only

In reality, the compromises between the Taliban and local communities are perhaps most evident in the limited level of crop destruction itself. High-resolution satellite imagery shows that eradication results are at best inconsistent. They certainly do not match the claims made by the Deputy Governor, who argued on 17th May that as many as 40,000 jeribs of poppy had been destroyed (the equivalent of 8,000 hectares), nor the videos circulating on social media and the local news showing swathes of eradication in the lower valleys of Argo, Faizabad, Jurm, and Daraya.

Rather, high-resolution imagery from 1 June 2024 over the central parts of Faizabad and Argo shows a patchwork quilt consisting of some poppy fields that have been destroyed, others where only some of the crop has been damaged, and many more where the poppy remains completely untouched (see Figure 5 and 6). It shows clear evidence that substantial amounts of poppy remain in central Argo in areas where the authorities claimed that all the poppy had been destroyed. There were also large numbers of fields left untouched in the villages around the provincial centre of Faizabad. In both cases, the effective eradication rate (where all the crop is destroyed) was less than 3% of the area grown with poppy (see Figure 7). Imagery shows no discernible pattern to the eradication, and clearly contradicts claims that none of the crop was spared.

Figure 5: Imagery analysis of poppy eradication for central Argo, Badakhshan, 1st June 2021.

Figure 6: Imagery analysis of poppy eradication for central Faizabad, Badakhshan, 1st June 2021.

Figure 7: Graph showing an imagery-based assessment of the effectiveness of eradication efforts in central Argo and Faizabad as of 1 June 2024.

Of course, an eradication campaign that leaves a significant part of the crop intact can serve two purposes. Firstly, it leaves farmers with an income they would not have otherwise had, reducing the economic impact of crop destruction and the risk of resistance in the area and potentially elsewhere; a chain of events the Taliban are all too familiar with given how they exploited local opposition to eradication as insurgents. Secondly, destroying only a small amount of the poppy crop lessens the threat of attacks on the eradication team by reducing the amount of time it spends in the area. There is also a possibility that an understanding was reached between community elders and the authorities that some of the crop would be left, despite Fasihuddin’s public protestations that all the poppy would be destroyed without exception. The authorities certainly put considerable effort into using the media to present the campaign as robust and effective to the outside world.

In fact, media accounts talked of up to 1,000 men deployed across the province, and video footage show eradication teams of 50 to 60 wielding sticks against a poppy crop that is approaching the flowering stage. However, controlled experiments in the UK, as well as experience in other provinces of Afghanistan, suggests that destroying the crop this way requires considerable physical effort; it can take as many as 20 people eight hours to eradicate one hectare.[ii] A team of 1,000 men would take 160 days to achieve the level of destruction the Deputy Governor claimed, yet the full eradication team had only been deployed in Badakhshan for little more than a week.

Eradication with tractors is more effective than sticks but requires a large number of such vehicles to be deployed along with the necessary logistical support, none of which was evident in Badakhshan. Moreover, video footage suggests tractors are being used sparingly. In most cases, the tractors would have to be driven across fields of wheat, bean, onion, and other crops to reach the large amounts of poppy that are not at the roadside, a practice that prompted some of the ill-will and resistance in Argo and Darayem in the first place.

Mounting an effective eradication campaign in Badakhshan is also made more difficult by the prevalence of a spring crop including in the more remote parts of the province. Planted at the end of March and early April, the spring crop is at too early a stage to be affected by eradication efforts mounted in May and early June; it is too small to be effectively damaged by stick, and if ploughed by a tractor, it can be irrigated, fertilised, and recovered, allowing a yield to be taken. An effective eradication campaign against the spring crop would need to be mounted in July but would need to be delivered in some of the hardest to reach parts of the province with little road access, and there is little evidence of this to date (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Imagery analysis showing the proximity of poppy to primary roads in Badakhshan in 2023.

Unsustainability of the poppy ban in poorer areas like Badakhshan

Farmers in Badakhshan do not have the large landholdings seen in south and southwestern Afghanistan. Consequently, they missed out on the benefits that landed farmers in Helmand and Kandahar have gained from holding opium stocks which have dramatically increased in value since Haibatullah announced his drug ban in April 2022 (see Figure 9). Rather, farming in Badakhshan is much more marginal. Most farmers own little more than half a hectare of irrigated land and, even then, cultivate some of their land with wheat to secure a partial food source for both their family and their livestock, as a hedge against a disruption to supply from outside to this remote mountain province.

In Badakhshan’s climate and geography, agricultural alternatives to poppy consist largely of kidney bean, potato, and onion. These are rarely grown on much more than 2,000 square metres of land (1/5 of a hectare) earning only as much as $600, half what would have been earned were to be poppy grown on the same amount of land prior to 2022 and the dramatic rise in prices that followed Haibatullah’s decision to announce a ban, and a sixth of what could be earned from a successful poppy crop this year.

Figure 9: Graph showing net returns on poppy cultivation in 2021,2022, and 2023, differentiating by land ownership and time of sale.

Non-farm income opportunities are also extremely limited in Badakhshan, restricted by the harsh winters and the collapse of the Afghan Republic. In the past, Badakhshan, received more development monies than it does now, stimulating the local economy and creating local employment opportunities. The Afghan National Army and Police also provided employment opportunities for large numbers of Badakhshi families. In provinces like Badakhshan these kind of jobs proved critical to the survival of the land-poor in the absence of poppy cultivation but have been lost since the Taliban takeover.

Eliminating poppy in Badakhshan would further reduce the local wage labour opportunities created by weeding and harvesting the crop. A labourer can earn as much as US$380 over the poppy season working in neighbouring districts, a critical income for the land-poor. The loss of this employment would have a deflationary impact on wages in the legal economy by greatly increasing the number of people looking for work, further impoverishing some of the most vulnerable.

There is little doubt that efforts to destroy the poppy crop in 2024 have increased tensions in the province. No matter how inconsistent the eradication campaign may be, there will be farmers who have lost some or all their crop and suffer economic hardship. Some are the same farmers who lost their crop last year or refrained from cultivation because they have land by the roadside that can be easily seen and reached by eradication teams. Viable alternatives to poppy (and in some cases hashish) are unavailable in the area, household debts are common, and farmers appear to have few options but to leave for Iran in search of work.

In such an environment, there will be growing resentment towards the Taliban authorities for failing to recognise the severe economic consequences of an effective ban on cultivation and for persisting with their desire to conduct a robust eradication effort. Resentment is heightened by the fact that the local opium trade continues unabated, with rumours that it is dominated by southern Pashtoons. The installation of the new Governor and the replacement of many Badakhshi officials by Pashtoons in the provincial administration, further fuels the perception that there is an ethnic bias within the Taliban leadership that is increasingly being imposed upon the provinces.

There is a high risk that farmers will yearn for a return to a level of insecurity that would allow them to grow poppy without risk of eradication, as was the case at times under the Republic. Experience, including that of the Taliban during the insurgency, shows this is a scenario in which armed opposition groups can flourish. The Islamic State Khorasan Province and the National Resistance Front already have a foothold in the province. Especially in a remote province, with so few viable economic alternatives, an aggressive eradication effort could drive more people to support these and other opposition groups. It is perhaps for these reasons that there has been a much more moderated effort at eradication by the Taliban authorities in Badakhshan this year, one that stands in stark contrast to the one presented in the media.

The Taliban authorities in Kabul and Kandahar will also recognise that they need to tread carefully with Badakhshi commanders if they are not to alienate them further. The Taliban leadership has perhaps already overreached in a desire to weaken local power structures by replacing so many Tajiks with Pashtoons in the provincial administration. While at this point, Badakhshi commanders may not wish to publicly challenge Mullah Haibatullah’s drug ban and the Governor’s recent efforts to destroy the crop, being seen to side with or acquiesce to a comprehensive eradication effort would not align with the interests of their rural constituencies or indeed many of their own soldiers who come from the villages being targeted. A more tempered eradication, where there is more heat than light, allows these commanders to be seen as serving the needs of their communities while maintaining the appearance of loyalty to the Emir.

Yet, at the same time, the Taliban need to be seen to be overcoming the public dissent that broke out in Badakhshan if unrest and a return to poppy cultivation are not to occur elsewhere. The endurance of the poppy ban also demands that authorities are seen to be countering the anomalous situation in Badakhshan, where cultivation is widespread. A failure to do so could result in the exception becoming the rule and farmers in other provinces returning to poppy cultivation in large numbers. Currently, the exaggerated accounts of crop destruction would appear to be part of the fiction that allows everyone to save face in the unfolding drama in Badakhshan.

Conclusion

While the fragility of the poppy ban is most obvious in the province of Badakhshan where widespread cultivation remains, there is little evidence that farmers in other provinces have made a permanent shift away from poppy cultivation, and the risk of a resurgence remains high.

High resolution satellite imagery indicates that further reductions in poppy cultivation will be achieved in Afghanistan in 2024, despite persistent widespread planting in Badakhshan. As of 22nd July 2024, crop mapping has been completed for 14 of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces, including the major producers in the south and southwest: Helmand, Kandahar, Uruzgan, and Farah, Nangarhar in the east and Baghlan in the north. These 14 provinces were responsible for 92% of the country’s total poppy cultivation in 2022, cultivating 201,725 hectares out of a total of 219,978 hectares grown. In 2023, cultivation in these provinces had fallen to 15,648 hectares (50% of the crop that year) and in 2024, only 3,641 hectares of poppy were grown (see Figure 10).

Figure 10: Graph showing estimates of the total land dedicated to poppy in 14 provinces, 2019-2024 .

At the same time, imagery analysis shows only minor increases in annual horticultural crops since the poppy ban has been imposed, and a significant reduction in perennials such as orchards and vineyards. In fact, the land dedicated to orchards has fallen by half in the two years since the drug ban was imposed, and vineyards by as much as one-third, with the provinces of the south and southwest hardest hit. Yet these are precisely the cash crops that combined with non-farm incomes offer a viable, sustainable alternative to opium poppy cultivation, and are the alternative much touted by the United Nations.

Instead, opium poppy has been replaced with wheat, along with a significant increase in fallow land; the implications of these shifts are significant (see Figure 11 and 12). Unlike a move to perennials, where there are significant sunken costs and farmers must typically wait anything from three to five years to obtain a harvest, a shift to an annual crop like wheat does not indicate an enduring transition away from poppy.

For example, whereas farmers have proven more reluctant to cut down their vineyards or pomegranate trees due to the expenses they have already incurred, they can quickly replace an annual crop with poppy once conditions allow. Replacing poppy with wheat represents a short term strategy in response to the ban; an indicator that farmers’ lack the confidence in both the market demand for high-value perennial crops, and that the poppy ban will continue, and are therefore reluctant to make a more permanent shift out of poppy.

Figure 11: Graph showing estimates of the total amount of agricultural land in 14 provinces, 2019-2024.

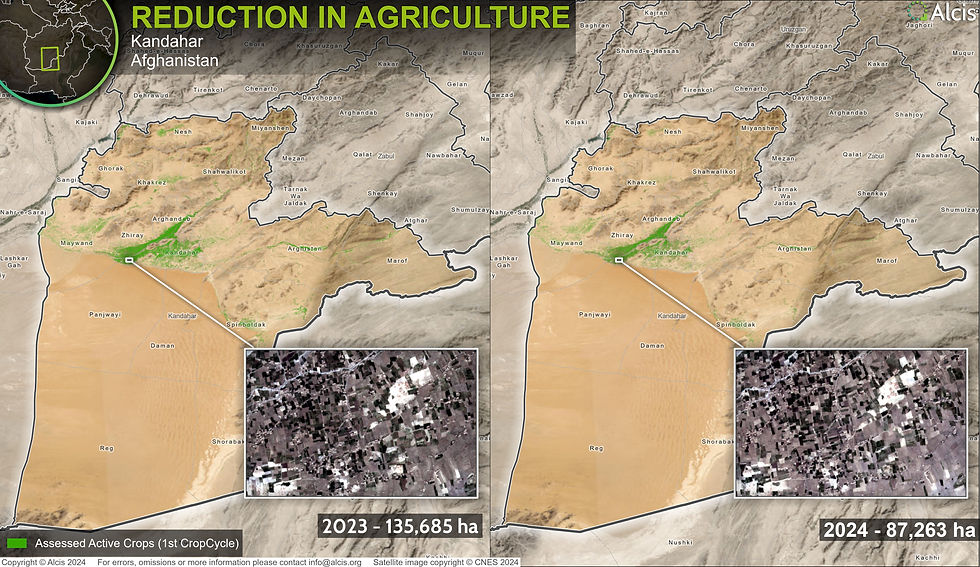

Figure 12: Imagery analysis showing the reduction in the amount of agricultural land in Kandahar between 2023 and 2024.

Moreover, most farmers in Afghanistan do not have sufficient land to grow enough wheat to meet their family’s food requirements (a large part of which comprises of bread), let alone to generate a surplus to cover their other household expenses. Consequently, a shift from poppy to wheat imposes significant hardship on those with small landholdings, especially where they do not have access to non-farm income, or assets they can sell to make up for their food and income deficit.

Here again we see how the ban favours some areas and population groups and disproportionately harms others, and is likely to lead to growing social and political tensions that will become increasingly difficult for the Taliban to manage, as they have found in Badakhshan. Livelihood analysis points to the growing challenges that farmers in more densely populated and mountainous rural areas face where landholdings are often less than one hectare of land. This stands in contrast to the south and southwest where imagery analysis suggests average farm sizes in the surface irrigated areas are typically 2.2 hectares, and in the former desert areas 4.89 hectares (see Figure 13).

Figure 13: Imagery analysis showing the amount of agricultural land and the number of households in the south and southwest of Afghanistan.

As our previous work has shown, with landholdings in excess of 2 hectares, landed farmers in the south and southwest can typically surpass the international poverty line of US$2.15 per person day from farming even in the absence of poppy, and draw upon the opium stocks they have accrued from intensive poppy cultivation over many years, to meet further household expenses, such as medical costs, marriage, or the purchase of a motor vehicle (see Table 1).

Imagery analysis suggests that there are around 285,425 rural households in the south and southwest, of which an estimated 70% - the equivalent of 1.75 million people - are landed, are likely to have retained some opium stocks, and have therefore been advantaged by the Taliban drug ban. This population is substantial and influential, and the poppy ban is popular with many of them, but their numbers will decline as the ban continues and their opium inventories deplete. However, in places like Badakhshan, where few households own substantial land or hold inventories, greater levels of coercion will be required to sustain the ban in the future given the absence of viable economic alternatives, particularly jobs for the land poor. In time this will prove increasingly destabilising.

David Mansfield has been conducting research on illicit economies in Afghanistan and on its borders each year since 1997. David has a PhD in development studies and is the author of “A State Built on Sand: How opium undermined Afghanistan.” He has produced more than eighty research-based products on rural livelihoods and cross-border economies, many for the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit, and working in close partnership with Alcis. David was also the lead researcher on the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction’s Counter Narcotics: Lessons from the US Experience in Afghanistan, covering the period from 2002- 2017.

[i] The fourteen provinces were Baghlan, Balkh, Daykundi, Farah, Helmand, Herat, Kandahar, Kapisa, Kunar, Laghman, Nangarhar, Nimroz, Uruzgan, and Zabul.

[ii] Cranfield University, 2005, ‘Effectiveness of opium poppy eradication using selected hand, mechanised and chemical techniques, at different stages in the growing cycle’, Unpublished Summary Report for HMG, September 2005.

Comments